Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus, left) and kangaroos (Eastern Grey Kangaroo, Macropus giganteus, right) are the most familiar representatives of Diprotodontia. Images © 1995 Greg and Marybeth Dimijian.

Introduction

The Order Diprotodontia is the largest order of marsupials. This order represents 11 families and over 110 species, including kangaroos, wallabies, possums, koalas, gliders and wombats. This order is very diverse in terms of size and habitat.

Classification

| Kingdom | Animalia |

|---|---|

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Subphylum | Vertebrata |

| Class | Mammalia |

| Order | Diprotodontia |

| Families |

|

Defining Characteristics

At first glance, members of the order Diprotodontia look very different from each other. For example, the possum looks very different than the kangaroo. The koala looks very different than a glider. However, all of these very different animals share two central characteristics that define diprotodonts.

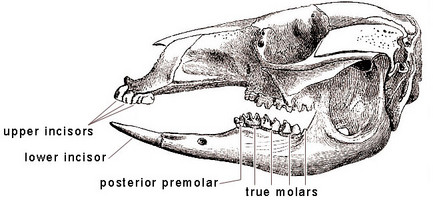

As you may have guessed from the name diprotodont, one of the defining characteristics has to do with the teeth of these animals. All members of Diprotodontia exhibit a large pair of incisors on the lower jaw. Most diprotodonts have 3 pairs of incisors in the upper jaw, and some have a second pair of small incisors in the bottom jaw. Diprotodontia also do not have canine teeth, instead have an empty space where these teeth should be. This unique dental pattern can be explained by the diet that these animals have. Diprotodonts are herbivores, so the sharp front teeth are used for cutting up pieces of grass and leaves to be eaten. The lack of canines exist simply because they have no use for these teeth. Canines are usually used for tearing meat, so these type of teeth are of no use for plant-eaters.

Skull of Bennett's wallaby, Macropus rufogriseus. Note the large incisors that dominate the lower jaw, as well as the gap where canine teeth are in other mammals in the upper jaw.

The second defining characteristic is a condition called syndactyly in the hind limbs. Syndactyly means “fused fingers” and is the medical term for webbed or conjoined digits in humans. In diprotodonts, the second and third digits of the feet are completely fused together, except for the claw.

The hand (top) and foot (bottom) of a koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Note how the syndactylous foot has the 2nd and 3rd digits fused together, but with two separate claws (arrow). Image © 2007 Sanjay ach

Habitat

Diprotodonts are native to only Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea and surrounding islands. They can be found in a wide variety of terrestrial habitats that are vastly different. Everything from grasslands to forests and even up in the mountains where it snows the majority of the year. Many members of this order have evolved to fit their specific habitat. A good example of this is the extra flaps of skin that exist in gliders. Gliders tend to live in heavily forested areas, and these flaps of skin act like sails allowing them to “glide” from tree to tree. This uses far less energy than jumping or climbing up the trees would. Another interesting example of this type of adaptation is the prehensile tail that can be observed in possums. This tail allows them to easily hang from trees.

Diet

Diprotodonts follow a mainly herbivorous diet, although some species are known to eat insects in order to supplement their diet. Some diprotodonts have evolved some interesting adaptations that allow them to get by on a diet of leaves and foliage that provide very little nutritional value. Some species have developed a longer digestive tract to allow them to absorb as much of the nutrition out of the leaves as possible. Other diprotodonts have developed habits that reduce the amount of energy that they need. For example, the koala will sleep for more than 80% of the day in order to conserve energy.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Perhaps the most commonly known characteristic of Diprotodontia and all marsupials is their unique reproduction as compared to other mammals. As a model for marsupial development, let’s consider the kangaroo. Marsupials have a very short gestation period, typically between 28 and 35 days. At this time the offspring is just a couple of centimeters long and is completely blind, but is still able to crawl to the mother’s pouch. The mother does little to help her young get to the pouch, except female kangaroos are sometimes observed licking up the path that the young will follow. However, this is not to guide the young as you may think, but to ensure that the young does not completely dry out before it reaches her pouch.

When the offspring finally reaches its destination, it attaches to one of the mother’s teats, where it will stay attached, unable to release for about 70 days. After the 70-day mark, the young can voluntarily release and reattach to the nipple. After 100 days in the pouch, the developing joey begins to move around, and it can open its eyes around the 130-day mark. The whole time the developing offspring is in the pouch the mother will care for it by periodically cleaning the pouch and licking the young. It is suggested that this licking by the mother stimulates waste excretion through the skin of the young. The mother licks this waste off the young, which actually recycles about a third of the water that was put into milk development by the mother.

After 4-5 months in the pouch, the head of the joey emerges. However, it is not until the joey is around 6 months old that it will first venture completely out of his mother’s pouch. Up to about 8 months of age, the young joey will use its mother’s pouch for warmth and nutrition, until the mother will prevent the joey from getting into her pouch by holding it shut when an attempt to enter is made. The joey will continue to nurse from the mother for another 4 months, until about 1 year of age.

Kangaroo mother with joey in pouch. © 2006 Robert Parviainen

The young kangaroo reaches sexual maturity at approximately 2 years of age, and will live for up to 20 years.

Marsupials also differ from placental mammals in their reproductive anatomy. Both males and females have bifurcated sex organs. Females have two lateral vaginae that function to transport sperm upwards, but not to deliver young down. Birth occurs through a pseudo-vaginal canal that acts as a shortcut to the outside. This canal opens and closes with each birth. Males posses a double-pronged penis matching up with the paired vaginae of females.

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site