© frogerin2 Hello, this is a picture of me, Fred the Pacific Treefrog.

Chapter One: Introduction

Hello, my name is Fred. I am a Hyla regilla. Do you know what that is? Well, it means that I am a Pacific Treefrog. If you live on the west coast of North America, you have probably seen me or one of my buddies around. Even if you have not, this scrapbook I have made about my life will tell you everything you could ever want to know about Pacific Treefrogs. In my scrapbook, you will find out about how I was born, what I look like, where I live, what adaptations I have made to my environment, my contribution to my ecosystem, my mating habits, and what happens in the average day in the life of a male Pacific Treefrog.

Chapter Two: How was I born, and how did I grow?

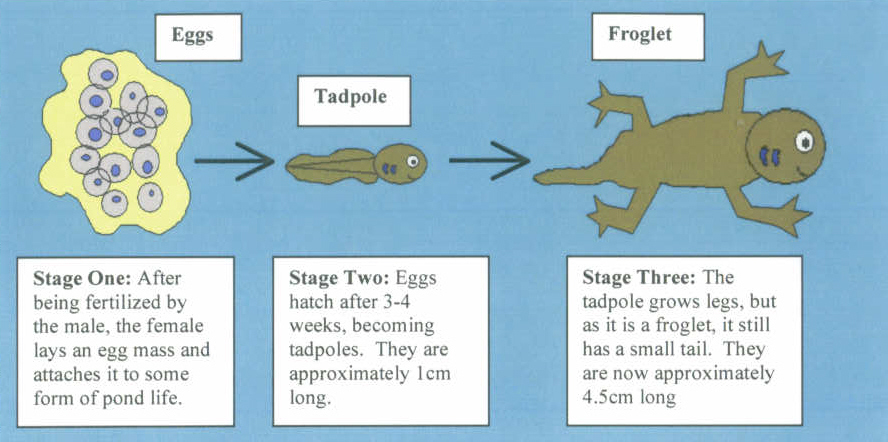

I was born in a temporary pond in southern British Columbia. A temporary pond is a pond that is only there for part of the year; it dries up when summer comes. Because I was born in this type of pond, there were fewer predators that could have eaten me while I was a tadpole, such as bullfrogs and fish. After my mother laid her eggs, my parents left because Pacific Treefrog parents do not stay to raise their offspring. After about three weeks, I hatched and became a tadpole, but I was only 1cm long! As I grew I ate algae and detritus (waste) that I found in the pond. Soon I grew into a froglet; I grew legs and my tail started to disappear. I was now 4.5cm long, and almost a fully mature adult Pacific Treefrog. A year after I was born I had become the full size of an adult frog, 5cm. I was also able to reproduce.

This diagram shows the growth process that all Pacific Treefrogs, like me, go through for the first few months of their lives. © frogerin2

Chapter Three: What do I look like?

Being a Pacific Treefrog, there are several characteristics that set me apart from other frogs. I am green in colour, but some of the other frogs I have seen and mated with are grey, tan, or even bronze. When the temperature or humidity around us changes, we can also change between lighter and darker shades of our original colour. For example, when the temperature changes, I can become either a lighter or darker green. I also have a cream coloured belly, and a dark yellow throat. Female Pacific Treefrogs have a lighter coloured throat. I have a V-shaped pattern between my eyes, which easily distinguishes me from other types of frogs. The black stripes that start at my nose and then extend to my eyes and shoulders are also defining characteristics. You can also tell that I am a Pacific Treefrog by the dark spots on my back and legs. My feet also have very distinct features. Unlike many frogs, I do not have webbed feet. My toes have round sticky pads that help me climb trees. Finally, my croak is also very different from other frogs, just click the link below if you would like to hear it.

Chapter Four: Where do I live?

My common name tells you a lot about myself. I am a Pacific Treefrog, so I live near trees or in plants on the Pacific coast of North America! I can live as far north as British Columbia, and as far south as Baja California. Within that area, I can live near the coast, in forests or rainforests, on farmland, on the top of mountains, or even in deserts! However, I prefer to live in areas that are cool and moist. In fact, when it gets too hot and dry, I have to live much lower to the ground, and I even become nocturnal, meaning I sleep during the day and am awake at night. I have to do this, because I am an amphibian, so my body temperature depends on the temperature around me, and I do not like to be too hot. Being nocturnal keeps me cool when my surroundings are too hot. Regardless of temperature, though, I do not like to live more than two feet above the ground. I guess you can tell by now that I do not live on the top branches of trees!

Chapter Five: How have I adapted to my environment?

In general, we Pacific Treefrogs do not take a long time to grow. In fact, within one or two years after our birth, we have reached adulthood! This is because we adapt so quickly to our environment. For one thing, we can change colours! We change colours to camouflage ourselves against dangerous predators, like other amphibians, or in response to changes in temperature or humidity. In fact, when there is an increase in temperature or humidity, we do not lose as much water, so we do not become dehydrated. As well, in efforts to stay cool, if the air is too hot and dry for us, we become nocturnal. Perhaps the most important adaptation that we have made to our environment is the large, sticky pads on the bottom of our toes. Can you see them in the picture below? They help us cling on to leaves and plants, and, acting like suction cups, we are able to grip and climb plants very well. This helps us out a lot when we are hunting for food or trying to escape predators!

Chapter Six: How do I contribute to my ecosystem?

As a Pacific Treefrog, I contribute greatly to my ecosystem. The major way I do this is by being an active member of my food web! You may be wondering what that means. Well, there are many organisms that would like to eat me or one of my buddies, and some of them do. Examples of these organisms are fish, and larger amphibians, such as salamanders and other frogs, like bullfrogs. Also, when we are tadpoles, water bugs, diving beetles and other frog tadpoles eat us. I know this sounds awful, and I agree- it is really sad when a fellow Pacific Treefrog is eaten. But we can also look at it like we are contributing to the ecosystem! After all, if these organisms did not eat us, what would they eat? How would they survive? And, of course, we do our fair share of eating too. In our growing stages, we are plant eaters, and eat primary consumers (this just means any organism that makes it own food, like plants do) such as detritus and algae. For our final month of growing, we do not eat at all, because our digestive systems are changing us from plant eater to insect eaters, because once we are adults, we eat insects! For example, we eat beetles, spiders, ants, and leafhoppers- yum! By eating insects, we control their population. Imagine, if Pacific Treefrogs did not exist, there would be too few fish, salamanders, and bullfrogs, and too many insects!

Chapter Seven: How do I reproduce?

The mating season for Pacific Treefrogs is from January to May. Usually, we are solitary creatures, but at this time us males get together and call the females to mate. The females can hear our call from even a mile away from where we are! We meet in temporary ponds to lay our eggs. When I mate, I put my feet on the waist of the female, and release my sperm. Then the female releases her fertilized eggs in egg clusters of about 10-70 eggs. She then attaches this cluster to a plant in the temporary pond, where the eggs remain until they are hatched. Once the eggs have been laid, my mate and I leave our offspring at the temporary pond and return to our homes.

© frogerin2 This is what our offspring look like when they are just tadpoles, growing into adult Pacific Treefrogs.

Chapter Eight

What is an average day in my life like? A day in my life is typical to that of other Pacific Treefrogs. We are, for the most part, nocturnal creatures; this means that we sleep in the day, and are awake at night. My night begins when I wake up. I usually sleep in a log or on a rock in the forest. Because Pacific Treefrogs are solitary, I live alone. After I have woken up, I usually hop around from rock to rock for a while. Then I begin trying to find food for the day. As I said earlier, my diet consists mainly of small insects such as gnats, mosquitoes, and flies. I have a long tongue that is covered with a sticky secretion that helps me catch these flying creatures. When I see an insect that I want to eat, I stick out my tongue really quickly so that I can bring the food back to my mouth. At night though, I also have to watch out for predators. Because I am so tiny, even other frogs, such as bullfrogs, can eat me. I also have to be careful of birds and other small mammals. The ones I fear the most are raccoons. A few days ago I was just hopping along when one took a swipe at me with his paw. He almost caught me but I kept jumping so I could escape. I took refuge in a nearby pile of rocks; luckily I escaped with only a scratch on my back. Other than my raccoon incident, I have been pretty fortunate. After an eventful night of catching flies and avoiding raccoons, I find a rock cluster or log to sleep in. I rest there for the whole day and wait for night to come again.

Epilogue

Well, I hope that by reading “Memoirs of a Pacific Treefrog,” written by me, Fred, you know more about Pacific Treefrogs than you did before! Did you read anything in particular that really interested you? If you did, I would sure love it if you shared it with your classmates- I like when people know who I am! And, just in case you cannot wait, here are a few more quick facts about Pacific Treefrogs:

- We call/croak for two reasons- one, to tell other males that this is “our territory,” and two, to attract female mates.

- We have not expanded the boundaries of our habitat too much, because the Pacific Ocean and various mountain ranges on the West Coast of North America keep us contained.

- We mate in temporary bodies of water, called “ephemeral” wetlands (an example of this is a puddle).

- While this keeps predators away from the young, sometimes these wetlands dry up before the young have time to grow.

- We are sometimes called Pacific Chorus Frogs (that would be Pseudacris regilla instead of Hyla regilla) because we croak in unison when calling for mates.

- Our Linnaean system classification is:

- Domain: Eukarya

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Craniata

- Class: Amphibia

- Order: Anura

- Family: Hylidae

- Genus: Hyla

- Species: Regilla

Information on the Internet

- The Pacific Tree Frog

- The Biogeography of Pacific Tree Frog (Hyla regilla)

- Hyla Regilla (Pacific Tree Frog)

- Pacific Tree Frog, Pseudacaris regilla

- Pacific Tree Frog, Pseudacaris regilla

- “tree frog.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Last updated: 2005. Encyclopædia Britannica [Online] Available http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-9073277, October 13, 2005.

Listen to tree frog

Listen to tree frog Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site